Now Reading: The Sphinx of Balochistan: Pakistan’s Silent Stone Sentinel

-

01

The Sphinx of Balochistan: Pakistan’s Silent Stone Sentinel

The Sphinx of Balochistan: Pakistan’s Silent Stone Sentinel

Deep in the rugged landscapes of southwestern Pakistan, far from the bustling cities and beaten tourist tracks, lies a mysterious formation that has intrigued travelers, geologists, and mystics alike. Known as the Sphinx of Balochistan, this natural rock formation bears an astonishing resemblance to Egypt’s iconic guardian of the Giza Plateau. But unlike the ancient sculpture of Pharaohs, this silent stone figure was sculpted not by hands, but by the slow, sculpting forces of wind, rain, and time.

Where Earth Meets Enigma: The Location

The Sphinx is located in Hingol National Park, Pakistan’s largest national park, sprawling across 6,200 square kilometers of stark, surreal terrain. Nestled along the Makran Coastal Highway, between the towns of Ormara and Pasni, the site lies approximately 240 kilometers west of Karachi. The area is part of the Makran coastal belt, known for its dramatic cliffs, golden beaches, and mud volcanoes.

This region is largely uninhabited, and its isolation has helped preserve its raw, untouched character—a canvas of geological wonder that seems plucked from a fantasy world.

Sculpted by Nature: The Formation of the Sphinx

Despite its lifelike features—a forehead, nose bridge, eye ridge, headdress, and crouched body—the Sphinx of Balochistan is a completely natural formation. Geologists classify it as an example of differential erosion, a process where softer rock erodes away more rapidly than harder layers, leaving behind unusual and often anthropomorphic shapes.

The Sphinx sits atop a sedimentary rock cliff, formed over millions of years through the accumulation and compression of marine sediments. The region is part of the active Makran subduction zone, where the Arabian Plate is diving beneath the Eurasian Plate, creating uplift and exposing ancient seabeds to the elements.

Through the ages, wind-blown sand, occasional monsoon rains, and temperature extremes have etched intricate shapes into the cliffs. The result is this uncanny stone guardian, frozen in time.

Myth, Mystery, and Misinterpretation

The human brain is hardwired to recognize familiar patterns in nature—faces in clouds, animals in rock outcrops. This psychological phenomenon, called pareidolia, explains our fascination with formations like the Sphinx of Balochistan.

While some fringe theorists have speculated that the Sphinx might be an ancient man-made structure—perhaps the weathered remains of a forgotten civilization—there is no credible archaeological evidence supporting such claims. Pakistan’s archaeological record, though rich with sites like Mohenjo-daro and Mehrgarh, contains no known culture that constructed monumental rock sculptures in this region.

That said, the sheer lifelike symmetry of the formation is remarkable. It challenges our assumptions about what nature can (and cannot) create unaided.

Unusual Geological Facts

Here are some lesser-known and surprising geological features of the area:

Living Mud Volcanoes

Hingol National Park has over 10 active mud volcanoes, some constantly bubbling. These are low-temperature features, rich in methane and hydrocarbons—unusual and rare globally.

Locals revere some as sacred and even leave offerings. The largest, Chandragup, is part of Hindu pilgrimage rituals.

Salt Domes and Hidden Fossils

Beneath parts of the park lie salt domes—underground salt structures that push up over time.

The sedimentary layers occasionally expose marine fossils, including ammonites, mollusks, and foraminifera, from when the area was a shallow sea.

Earthquake Swarms

The region experiences frequent micro-earthquakes due to intense tectonic stress. Some have caused new fissures or temporarily reactivated mud volcanoes.

Spheroidal Weathering

Many of the strange rounded boulders in the park, resembling eggs or domes, are shaped by spheroidal weathering—a chemical process that rounds angular rocks over millennia.

In the Land of Natural Monuments

Hingol National Park is a geological museum without walls. Alongside the Sphinx, you’ll encounter:

Princess of Hope

A tall rock formation that resembles a robed woman gazing out to sea—its elegance named by Angelina Jolie during her 2002 UN visit.

Mud Volcano

Rare geological features where gas pressure causes mud to bubble up through fissures. These are sacred to local Hindu pilgrims and have been active for centuries

Kund Malir Beach

A surreal mix of blue-green surf, desert hills, and untouched coastline—arguably one of Asia’s most pristine beaches.

Buzi Pass and the Rock Forest

Wind-sculpted pinnacles and arches rise like forgotten ruins across the stony desert, some towering over 30 feet high.

Hinglaj Mata Temple

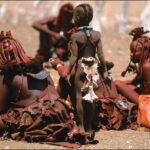

A revered Hindu pilgrimage site tucked deep in a canyon, attracting thousands of devotees each year.